Home |

Publications |

Calendar |

History of Cards |

New Issues |

Join IPCS |

Pay Subscription |

Members' Area |

Area Representatives |

FAQ |

Links |

![]() Follow @I_P_C_S

Follow @I_P_C_S

Playing cards are common, everyday objects which we take for granted. Yet they have a history of use in Europe which goes back to the late 1300s; their design is a strange mixture of fundamental changes as well as aspects which haven't changed since medieval times. They are found in almost every corner of the globe.

The design of the standard English playing-card is now well known throughout the world because of the spread of card games like bridge and poker. If these are the only sort of playing-cards you have come across you may think that there is only one basic design for the faces of cards, with just the design on the back varying.

You would be wrong! The English pattern is not the only design; most countries have their own designs, popular locally, which you may not have seen. These are very often far more colourful than the English one and beautifully printed. The composition of the pack often changes with the game which is being played; a Swiss players sitting down to play jass expects to find 36 cards in their pack, German skat players use 32 cards, while the dealer of French Tarot has to cope with 78 large cards in their hand. In many parts of the world, different suit systems sre in use, rather than the familiar hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades! And of course, packs are designed and printed especially for children's games-such as Old Maid and Black Peter.

This brief history is based on a leaflet prepared by John Berry to provide background for the Exhibition 'The World of Playing Cards' at the Guildhall Library, London, from September 1995 to March 1996.

English playing-cards are known and used all over the world - everywhere where Bridge and Poker are played. In England, the same pack is used for other games such as Whist, Cribbage, Rummy, Nap and so on. But in other European countries games such as Skat, Jass, Mus, Scopa, and Tarock are played, using cards of totally different face-designs many of them with roots far older than English cards. The history of these national and regional patterns has only recently

become the concern of students and collectors.

English playing-cards are known and used all over the world - everywhere where Bridge and Poker are played. In England, the same pack is used for other games such as Whist, Cribbage, Rummy, Nap and so on. But in other European countries games such as Skat, Jass, Mus, Scopa, and Tarock are played, using cards of totally different face-designs many of them with roots far older than English cards. The history of these national and regional patterns has only recently

become the concern of students and collectors.

As many travellers to more southerly parts of Europe can tell, the familiar suits of Hearts Spades Diamonds and Clubs give way to quite different sets of symbols: Hearts Leaves Bells (round hawkbells) and Acorns in Germany; Shields 'Roses' Bells and Acorns in Switzerland; Coins Cups Swords and Clubs (cudgels) in Spain and Mediterranean Italy; Coins Cups Swords and Batons in Adriatic Italy. In the latter region, in particular, local packs of cards have a decidedly archaic look about them - which reflects the designs of some of the earliest cards made in Europe.

The earliest authentic references to playing-cards in Europe date from 1377, but, despite their long history, it is only in recent decades that clues about their origins have begun to be understood. Cards must have been invented in China, where paper was invented. Even today some of the packs used in China have suits of coins and strings of coins - which Mah Jong players know as circles and bamboos (i.e. sticks). Cards entered Europe from the Islamic empire, where cups and swords were added as suit-symbols, as well as (non-figurative) court cards. It was in Europe that these were replaced by representations of courtly human beings: kings and their attendants - knights (on horseback) and foot-servants. To this day, packs of Italian playing-cards do not have queens - nor do packs in Spain, Germany and Switzerland (among others). There

is evidence that Islamic cards also entered Spain, but it now seems likely that the modern cards which we call Spanish originated in France, ousting the early Arab-influenced designs.

The earliest authentic references to playing-cards in Europe date from 1377, but, despite their long history, it is only in recent decades that clues about their origins have begun to be understood. Cards must have been invented in China, where paper was invented. Even today some of the packs used in China have suits of coins and strings of coins - which Mah Jong players know as circles and bamboos (i.e. sticks). Cards entered Europe from the Islamic empire, where cups and swords were added as suit-symbols, as well as (non-figurative) court cards. It was in Europe that these were replaced by representations of courtly human beings: kings and their attendants - knights (on horseback) and foot-servants. To this day, packs of Italian playing-cards do not have queens - nor do packs in Spain, Germany and Switzerland (among others). There

is evidence that Islamic cards also entered Spain, but it now seems likely that the modern cards which we call Spanish originated in France, ousting the early Arab-influenced designs.

In Germany and Switzerland, the two lower court cards are both on foot, representing an 'upper' and a 'lower' rank-as stated in the 1377 description of playing-cards. Switzerland also preserves another feature of early German cards. The tens are represented by a banner, showing just one suit-symbol-though many old German banners show ten symbols. In these countries also, the 52-card pack was shortened to 48 cards by dropping the Aces. The deuce, or Daus, was then promoted to being the top card, and nowadays often carries the letter A as if it were an ace. The pack was then shortened even further. German single-figure packs habitually carried delightful vignettes of genre scenes at the base of the numeral cards-usually lost when packs became double-ended.

In Germany and Switzerland, the two lower court cards are both on foot, representing an 'upper' and a 'lower' rank-as stated in the 1377 description of playing-cards. Switzerland also preserves another feature of early German cards. The tens are represented by a banner, showing just one suit-symbol-though many old German banners show ten symbols. In these countries also, the 52-card pack was shortened to 48 cards by dropping the Aces. The deuce, or Daus, was then promoted to being the top card, and nowadays often carries the letter A as if it were an ace. The pack was then shortened even further. German single-figure packs habitually carried delightful vignettes of genre scenes at the base of the numeral cards-usually lost when packs became double-ended.

How all these variations on the basic idea came about is not fully understood. One plausible theory is that some of them arose from midunderstandings due to language differences, which resulted in something like visual puns.

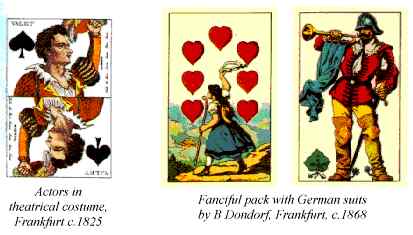

Alongside the evolution of these traditional designs, in most countries there have also been persistent efforts to publish more fanciful cards, either as artistic essays, or with some purpose other than simple card-playing: for example, instruction, propaganda, or even amusement. Following a French initiative, England in the late 17th and early 18th century produced a range of very idiosyncratic packs of cards of this type.

But other countries, such as Germany and Austria, became the chief 19th-century producers of packs of fanciful cards meant for use in card games in polite society.

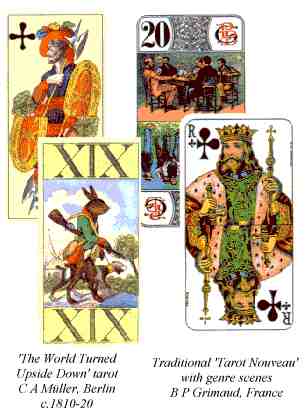

The study of the development of playing-cards has further been bedevilled by overmuch attention to tarot packs. To the best of our knowledge, the first packs of cards in Europe comprised 52 cards in four Italian-type suits each with three court cards (king, knight, and foot-servant), and were used for games of skill involving trick-taking, as well as for gambling games, which were often prohibited. Very soon, the idea of adding extra cards to act as permanent trumps came into being, and the tarot pack was born. At the same time a queen was interpolated between the king and the knight, so that, with the extra 22 non-suited cards, a pack of 78 cards was created. Such packs have continued to be used for their original purpose right through to the present day.

In the course of their long life, many variations have been tried: the pack has been extended to 97 cards for Minchiate by adding more trumps; shortened to 63 cards by dropping low-value numeral cards; converted to using French suit-signs; shortened to 54 and 42 cards by dropping numerals; but always with the object of playing trick-taking games. Many of these variants are still in use for just that purpose.

It is the choice of subjects for the trump cards which has been the focus for so much attention by both scholars and occultists. Though playing-card historians still do not have a satisfactory explanation of the sequence of subjects, many of the occultist theories have been discredited. For instance, the tarot pack was known in Europe in the early 15th century, before the arrival of the gypsies. This rules out the proposed connection with Egypt first put forward in 1781, which forms the foundation for much of the later occult speculation. The earliest known use of Tarot packs for fortune telling was in Bologna, around 1750, using an entirely different system of meanings, and the use of ordinary packs of playing-cards for cartomancy does not date from much earlier than this. Unfortunately, some occultists and cartomanciers continue to ignore these facts.

With the conversion of the tarot pack to the French suit-system, the trump cards, with their no longer understood imagery, were replaced by other sequences of pictures: animals, mythological subjects, genre scenes. The value of each trump card was now indicated by a large numeral (the forerunner of corner-indices), so that the pictures had no function other than decoration. However, a few sets of pictures found favour with card players, and gradually the range of such tarot packs narrowed down.

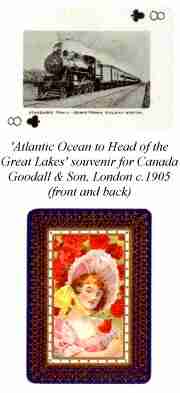

The use of pictures on tarot trumps was eventually copied in a modern development of the older idea of 'pictured' cards. (Indeed, a couple of tarot packs actually started life as normal packs of cards with pictures instead of pips on the numeral cards.) The success of this idea was dependent on the introduction of corner-indices-an American innovation which was surprisingly late in being introduced in view of much earlier experiments in that field. In America, around the turn of the century it was exploited in order to turn photographs of scenery into souvenir packs intended to promote the joys of rail travel. And such packs were further distinguished by colourful pictorial designs on the backs of the cards-which have lately become collected for their own sake. Many modern packs of cards use a similar format to carry 52 different pictures of all kind of subjects: animals and birds, views, works of art, cartoons, pin-ups, trains, planes, etc.

The 19th century also saw the development of a vast industry in cards which were meant to appeal to the public simply by being attractive-or topical-with courts drawn from literary, historical or contemporary figures. The fashion may have started as an offshoot of the 19th-century phenomenon known nowadays as transformation cards. The chief idea was to take the numeral cards of an ordinary pack and to make designs in which the shapes of the pips were an essential element.

The resulting cards were, of course, totally unusable for play when they had no corner-indices, and indeed the publishers of early packs recommended that the blank backs should be used as visiting cards (a very important item in high society). Nevertheless, almost from the beginning, court cards were also provided so as to complete the pack. In Europe these were drawn from literary sources, though in England a more humorous approach prevailed. It is probable that such ideas helped to propel a tendency for playing-cards to keep up with current fashions and trends. Even the more run-of-the-mill continental cards tended to have elegantly clad and fashionably coiffured ladies instead of crowned queens.

The resulting cards were, of course, totally unusable for play when they had no corner-indices, and indeed the publishers of early packs recommended that the blank backs should be used as visiting cards (a very important item in high society). Nevertheless, almost from the beginning, court cards were also provided so as to complete the pack. In Europe these were drawn from literary sources, though in England a more humorous approach prevailed. It is probable that such ideas helped to propel a tendency for playing-cards to keep up with current fashions and trends. Even the more run-of-the-mill continental cards tended to have elegantly clad and fashionably coiffured ladies instead of crowned queens.

The fashion was very slow to catch on in England. Despite a few experiments, mostly not very attractive, it was only with the use of chromolithography towards the end of the century that artistic packs became viable. But English card-players had a reputation for conservatism anyway-witness their great reluctance to change from single-figure court cards to double-ended ones-and even then the numeral cards were slow to follow suit. The usefulness of corner-indices seems to have been appreciated more quickly, however.

English card-players also clung to the traditional, but frankly ugly, designs of their court cards, which had remained virtually unchanged since before 1700. Prior to that era, we have scanty information about the designs of everyday cards, since few of them have survived. An English educational pack of 'Memory cards' of c.1605 includes copies of elegant court cards made in Rouen, where cards of a particular design were made especially for export to England. Study of these cards goes far to explain peculiar features of later English-made versions. The crudity of these copies was due to inept English block-cutters trying, with home-made products, to compensate for the effect of the 1628 ban on importation of foreign cards. In fact, the accidental stylisation has proved to be a functional factor of stabilising influence in ensuring the durability of these designs. Most modern English-style cards still betray signs of their ancestry.

English card-players also clung to the traditional, but frankly ugly, designs of their court cards, which had remained virtually unchanged since before 1700. Prior to that era, we have scanty information about the designs of everyday cards, since few of them have survived. An English educational pack of 'Memory cards' of c.1605 includes copies of elegant court cards made in Rouen, where cards of a particular design were made especially for export to England. Study of these cards goes far to explain peculiar features of later English-made versions. The crudity of these copies was due to inept English block-cutters trying, with home-made products, to compensate for the effect of the 1628 ban on importation of foreign cards. In fact, the accidental stylisation has proved to be a functional factor of stabilising influence in ensuring the durability of these designs. Most modern English-style cards still betray signs of their ancestry.

It was on 22nd October 1628 that Charles I granted the charter to the Company of the Mistery of Makers of Playing Cards of the City of London, and from 1st December that year all future importation of playing cards was forbidden. In return, a duty on playing-cards was demanded, and the subsequent history of attempts to extract that duty makes an unedifying and contradictory story, as any student of such matters knows. The Livery Company still exists,

and, despite the almost total cessation of production of playing-cards in Britain, flourishes. In 1994 it achieved its highest ambition in the City of London, when a former Master of the Company, Alderman Christopher Walford, became Lord Mayor. Towards the end of his term of office, he opened an exhibition of playing-cards in the Print Room at Guildhall Library, which houses a collection of historic playing-cards belonging to the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards, the nucleus of which was donated by the 'Father of the Company' Mr Henry Druitt Phillips, in 1907.

It was on 22nd October 1628 that Charles I granted the charter to the Company of the Mistery of Makers of Playing Cards of the City of London, and from 1st December that year all future importation of playing cards was forbidden. In return, a duty on playing-cards was demanded, and the subsequent history of attempts to extract that duty makes an unedifying and contradictory story, as any student of such matters knows. The Livery Company still exists,

and, despite the almost total cessation of production of playing-cards in Britain, flourishes. In 1994 it achieved its highest ambition in the City of London, when a former Master of the Company, Alderman Christopher Walford, became Lord Mayor. Towards the end of his term of office, he opened an exhibition of playing-cards in the Print Room at Guildhall Library, which houses a collection of historic playing-cards belonging to the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards, the nucleus of which was donated by the 'Father of the Company' Mr Henry Druitt Phillips, in 1907.

The Guildhall Library accepted on deposit a second important collection of playing-cards, owned by John Waddington PLC. This acquisition complements the previous collection in many instances in a very useful way, and considerably enhances the range of material available for study. Those collections are now housed at the London Metropolitan Archives in Clerkenwell. It is possible to search their catalogue.

This synopsis has dealt mainly with European cards though the Chinese origins have been mentioned briefly. China was, for many decades, rejected as the origin of playing-cards because its traditional cards are so unlike Western ones. The connection with coins, and strings / bamboos / batons, however, cannot be ignored. Other Chinese playing-cards (which they themselves regard as gambling cards) use systems rooted in dominoes and Chinese chess- and Rummy-type games which were not known in Europe until relatively recently.

Indigenous Japanese games rely on principles of 'matching' (involving a highly literary version of Snap) or on games involving cards which ultimately stem from European models -heavily disguised to evade prohibitions on gambling.

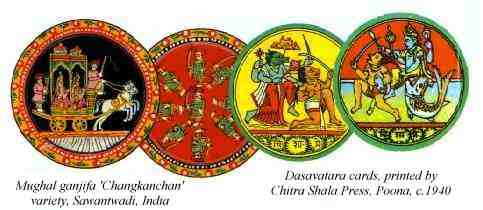

In parts of India, games are played with packs of circular cards with eight, ten or more suits, whose designs reflect either the departmental structure of an Indian rajah's court or the incarnations of Vishnu (or other more complex systems), and are played something like Whist with no trumps but with extra complications. Earlier this century, it was claimed that there was a connection between the four-suited European pack and the four-handed game of chess

played in India, but this theory has now been discredited in the light of the connection with the Islamic world.

In parts of India, games are played with packs of circular cards with eight, ten or more suits, whose designs reflect either the departmental structure of an Indian rajah's court or the incarnations of Vishnu (or other more complex systems), and are played something like Whist with no trumps but with extra complications. Earlier this century, it was claimed that there was a connection between the four-suited European pack and the four-handed game of chess

played in India, but this theory has now been discredited in the light of the connection with the Islamic world.